Thus far in our examination of the creative irrational as the key to individual consciousness and human success we have been primarily dealing with the insights provided by what might be called the humanities[1] as opposed to the natural sciences[2]. The former is most often considered irrational while the later is seen to be an ultimately rational undertaking. A search for the key to human success through a study of the irrational may strike the modern day Western reader as virtually unknown territory. We are for the most part raised in a world of technology based on an overwhelming perception of “science”. But it must be noted that science and the scientific method are very recent developments in the history of humans essentially beginning in the early 1600’s with the writings of Francis Bacon – the “father of empiricism.”[3]. It has been claimed for centuries that science, developed through the efforts of pioneers like Francis Bacon and Isaac Newton, is the prototype of the truly objective search for knowledge. Certainly the methods and outcomes of science have resulted in marked improvements in our quality of human life through advances in fields such as medicine and engineering. But buried beneath the apparent clarity of many of sciences’ answers, a number of outstanding questions remain hidden to the casual reader, buried if you will in a modern myth. The myth being that science is the logical rational application of scientific discoveries to improve the creations and constructions of human activities. While most average citizens get lost in the intricacies of finding a relevant testable hypothesis and what might ultimately result in a useful and productive conclusion, the key to science is the moments of creative thought by research that initiates and motivates the scientific method. As professional scientists we the authors have found in our struggles with idea generation is that the basis of science is much more irrational than is generally appreciated by non-scientist. In this regard, we can find that science and the humanities share a common basis in the role of the creative irrational.

In 1936, Einstein wrote, “The whole of science is nothing more than a refinement of ordinary thinking”[4]. He wrote this towards the end of a time period when a seemingly enormous gap developed between traditionalism and rationality as a result of the science of the 18th and 19th centuries. It was a time when old rationalities were being questioned in new ways required to understand nuclear science, sub-atomic particles and a unified space-time continuum. Early 20th century science has challenged many of the old beliefs in its search for new and improved understandings.

In a time when science and technology play such an central role in our life activity and our thinking, we the authors see a need to explore what has been commonly seen as an irreconcilable opposition between traditionalism and rationality. In truth can we validate any real opposition? Is there a viable basis for reconciliation? In this chapter we undertake to examine the methods and claims of science that have been created and reworked over time. We aim to better appreciate the underlying creative aspects of the scientific method and to present a brief state of scientific knowledge and to get some insights into what many in the modern Western World consider to be a familiar source of knowledge: sciences’ modern myths. There is much to be gained in our search for the creative irrational by developing a greater comprehensiveness and focusing attention on the all-important creative thoughts that we find at the initiation of any and all scientific investigations. Without a doubt which clarity bridges the perceived gap between the humanities and science.

What we shall see is that science relies on an impetus from much the same sources and questions as were tapped for the other examples of the creation irrational in human existence. It has given our society expectations that it can satisfy some of the same needs and desires as were served by past beliefs and efforts. By developing a broader comprehension of the basis of science, we can clearly see its struggle to initiate new and relevant perceptions of reality. A closer examination of the salient aspects of these two sources of knowledge, science and the humanities, shows that they share a single, common reality.

The Apparent Paradox between Science and the Humanities

An apt statement of the paradoxical points of view that have appeared between what is often cited among the humanist categories as “traditionalism”, and the “rationalism” that underlies science was made in a comparison of the medieval and the modern by West:

"There can be little doubt that the medieval concept of the world was one-sided. But the contempt in which the Middle Ages are now held is a measure of the misunderstanding of the epoch; and the result of a world view that is no less distorted.

To the modern Rational mind, the universe is a gigantic fact, reducible to an infinity of constituent facts. To the medieval mind it was a gigantic symbol; in which phenomena in all their diversity were but reflections of the will of God. Indifferent, or downright hostile to matters of fact, the medieval mind was interested only in the principle behind the fact. To the modern mind, only facts count and principles take care of themselves. The scientist distrusts or even denies the reality of inner experience.... He relies upon the evidence of his senses. If he can measure it, it is 'real'. The medievalist called the world of sense an illusion; only inner experience was real. He may have believed the world was flat but he understood the universe to be a hierarchy of values, because that was his experience. Our modern thinkers may know the earth is round, but they think value is `subjective`, a mere invention of man (perhaps because their own inner experience is so poverty-stricken and disordered they cannot trust it). The medieval mind ignored the facts of the physical world, and so produced a society that was all cathedrals and no sanitation. The modern mind ignores the value of the spiritual world and so has produced a society that is all sanitation and no cathedrals. Rationalists rejoice and call this progress. But the increasingly fraught psychological state of our sanitary society suggests that in the end cathedrals may prove to be the necessity, sanitation the luxury.” [5]

An inability to weigh the power of the medieval concern for the "ideals" of human value on the same scale as the modern concern for the "facts" of human welfare is a measure of the distance between two states of mind that might be held to typify two different civilizations. But it also vividly echoes the difference between the outlooks of the humanities and science. Under certain conditions it is possible to see the two views as valid and complementary rather than alternative and incompatible. But this requires a concept of the humankind that is quite different than either the medieval or the modern.

West’s remark is an appropriate starting place because it illustrates the unconscious limitations that are required for espousing either science or the humanities in our search for knowledge. Holding strictly to one viewpoint or the other does not allow the possibility of a productive resolution. Such was the case in the aggressively held views of the opposing teams in the debates about evolution between science and religion during the mid-19th century[6] and is still all too often evident, particularly in association with science literalism in contrast to religious fundamentalism.

To the inhabitants of the Middle Ages it was obvious that the world exists on least two different levels, specifically the world of humankind and that of God, the physical and the spiritual. Progress to the medievalist was in the nature of a change in state, amounting to a transformation of being from one level to another. That is, the aim of development of humans was a qualitative one involving movement from the physical towards the spiritual.

At present, in the name of literal science, we have commonly come to equate the physical with the real. The spiritual, equated with the humanities, is unreal and irrational and is represented in our stories and beliefs. As a result, in the sciences the idea of quality has been downgraded to the measurable attributes of things, such as their colour, texture, density and/or their price. Instead of transformation in a vertical direction, we were restricted to considering changes in attributes on a horizontal “physical” plane. The confusion of the qualitative with the quantitative was complete to the point where as literal scientists we can scarcely understand, and certainly cannot trust, the objectivity of such concepts as the value of beauty, love or comedy as we explored earlier in Chapter 6. In strictly rational terms, the value of beauty is something reflected in the price that someone is willing to pay for a "work of art." How much should one pay for a "recreational" experience of music or for a brief delving into the world of "Nature"? Until recently the latter was regarded as the subjective indulgence of appetite or habit - a holiday away from the real world of "work" and “action.” This attitude is changing with the attempt of environmental politics and economics to confer a significant value on ecological and social well-being[7].

Modern qualitative valuation redefined in this way is obviously still not adequately objective for the scientific view. It remains different between individuals and situations. It therefore offers only statistical criteria for the "objective" judgment that is the avowed aim of science. In short, in our so-called "modern" age, unmindful of the differences in the quality of the sense of self that arises with differences in level of perception, we have been taught to define all inner experience as subjective, hence transient and untrustworthy, thus irrational, while only the outer physical measurable world is objective, enduring and substantial thus rational. In this scientific world, progress is movement along an external horizontal gradient of matters, aggregated in different fashions and organized to different degrees of generality or homogeneity. From the point of view of the value or the purpose of a life, this is indeed a flat world, devoid of what could be called either depth or height.

From a point of view that is genuinely concerned with the value of life, this confinement of learning to a plane on which value is not a valid dimension is no alternative at all. The science of the beginning of the Renaissance may have been legitimately intent on escape from the subjectivity of vague notions of an external and only vaguely conceived, though personified, God who ran everything. Did our world extend only from birth to death, with a possible choice between hell or salvation? The effort to be free of such subjectivity fell into the extreme opposite of rejecting value from what was included in science. Reaction was so extreme that in the name of rationality science forgot that even physics and mathematics, in all their exactness, are the products of scientists acting through the only possible medium: individual and collective human interest and effort. This is subjective to the extent that it depends on the way humans work. With this as the dominant view, however, the possibility of finding a unity between subjective and objective approaches to knowledge and understanding was virtually lost.

The tragic result of this uncomprehending dichotomy was that in the 20th century the technical ingenuity and the exactness and precision of science were used to invent, construct and drop two atom bombs. There were no comparably "objective" criteria for determining how to control the obvious threats that this technology offered to the lives of all human beings or to their environments. An epistemology that leaves out of account the most important purposes of learning, surely invites rejection and replacement by a more comprehensive base of understanding. This was the position into which Western society plunged itself as another consequence of the 1945 dropping of atom bombs on Japan.

It is little wonder that in the second half of the 20th Century succeeding society has shown both a suspicion and a fear of science that, despite the excitement and attraction of space travel, feels a growing need to somehow weaken and control it. It is obvious that outright rejection of science or of the technology that comes from it, would forego its many benefits. Coincidently, the resolution of the dichotomy between it and the needs for human valuation began to emerge in the late 1920's at the time that science was beginning to make breakthroughs in sub-atomic physics and our understanding of the physical universe. To understand it and its importance requires that we probe more deeply into the nature and development of science itself and those who have led us to this point.

The Origins and Evolution of Science

Science as we have known it grew out of reaction to medieval intellectualism. Activities of “higher learning” during the Middle Ages or Medieval Period from the 5th to the 15th century in Western Europe thrived on debate and argument that invited subjectivity and division, not objectivity and common understanding. The result was an incipient chaos in Western Culture throughout the Dark Ages[8]. While speculation continued to be the very life-blood of scholasticism in philosophy and religion up to the beginning of the 16th century, the importance of direct observation rationality began to reemerge with the 13th century works of Roger Bacon, circa 1219/20 – 1292[9], and Thomas Aquinas, 1225 – 1274[10].

Bacon reintroduced Aristotle into medieval philosophy. Bacon expounded a view that mathematics was the gateway to science and that controlled experiment was the route to the verification of thought. His requirement for external objectivity based on observations and experiment was clearly distinguished from the faith-based and wisdom-based explorations that are the basis for internal truth and experience. Basically this was an early distinction between the operation of both the rational and irrational in the lives of humans.

In the same time period as Bacon was writing, Thomas Aquinas used Aristotle to support a view that faith and reason are complementary and harmonious approaches to reality, not opposites. Aquinas’ view of science was clearly much ahead of its time. The separation of scientific as externalized or exoteric, from internal or esoteric truth was probably necessary for religious followers of the period. Both aspects of his view initially persisted and grew. Eventually, however, the faith that was reflected in religious doctrines of the time was so subjected to divisions of interpretation and argument that the earlier sense of its importance was lost from what developed as “science”. The internal basis for arriving at truth was removed from serious contention with the external revelations of empiricism, even before science was fully developed.

But while Aquinas' view that included both faith and reason became official doctrine of the Roman Catholic Church, the dichotomy between an individual’s ability to receive higher levels of existence and the need for a religious intermediary, such as the church, continued to challenge medieval thought. Divisions between the church and the society continued to grow. The church couldn’t see its way to control the thoughts and behaviours of its followers if individuals were allowed to follow their own internal direct observations without the priest-based restrictions.

The best example of the threat perceived by the church of empowering humans to trust their own direct experience can be found in the life of the first proponent of presenting religious writings in the common language of the people rather than in Latin. The Dominican priest, Meister Eckhart, circa 1260 – 1328 wrote in the local German language of the day. As he was writing at the same time as Bacon and Aquinas, it is not surprising that Eckhart was also intimately acquainted with the philosophy of Aristotle. He urged all to seek god within themselves[11]. His history shows how the established church fought against his thoughts and against any possibility of an individual’s direct observations for a connection with their higher consciousness. As a result he was condemned for heresy. His condemnation by the established church was partly the result of the continuing reactions to a literal dictation of an ultra-moralism that, nevertheless, revealed chinks in the armour of those who held themselves responsible for administering it. Such chinks had already surfaced in 1233 by the papal Inquisition of Pope Gregory IX in an attempt to resolve the conflicts by destroying diverging views it defined as heresy. The use of such power has rarely succeeded in the long run, and ultimately failed in this case, but not before the atrocities it committed had become a lasting testimony to the potential bestiality that lives in humankind alongside our wished-for rationality. In the long-run such dicta increased the resistance to the old intellectual order. Although Echart’s teachings were not well remembered for centuries his history is a clear example of the early recognition by some individuals of the two sides of human existence: the rational found in external scientific observation and the irrational found in the power of faith and direct internal observation.

A fuller realization of modern science came only with Francis Bacon, circa 1561 -1626. His codification of the rules of experimental methods gave rise to an alternative that was able to challenge the established church for authority over western civilization’s worldview. His scientific concept of Utopia, described in his publication “The New Atlantis” of 1627, was credited with the formation of the Royal Society of London in 1660 – the first national scientific institution in the world. In this environment, recognized by royal charter by the established secular head King Charles II and cultivated by the efforts of such scientific giants as Sir Isaac Newton, science was perceived as guaranteeing that its own divisions and analyses were in the interests of generalization, which is widely accepted as a move towards Unity. Multiplication of objective facts gives rise to perceptions of the rules of nature that govern external phenomena. Phenomena, such as the movements of the planets, yielded to the explanations and predictions of science, hence science guaranteed that there is a dependable reality and possibly even implied that it would eventually be comprehended as a Unity.

The most famous example of the beginning of science and its usefulness at the time of Bacon and Newton comes from the beautifully simple example of an apple falling from a tree Even while being wrong in its basic model, the concept of gravity as an attractive force between objects is something that individuals can grasp and have a sense of directly. At the time it was inconceivable that 300 years later Einstein would exercise his creative irrational to imagine gravity as the curvature of the time-space continuum resulting from objects with mass[12]. Even the early approximate “Law of Gravity” of Newton evidenced forces so subtle and so powerful that it required a new concept of the gods themselves. There was little reason to try to reconcile such heady practical success with the confused longings that motivated the divisions apparent between “Science” and the “Arts and Religion”.

There is a certain irony in the fact that the ideal of the medievalist to approach wholeness was traded by science for a rationality that was designed from the outset to be "partial". This appears to us as irrational as the other human endeavors presented in this book. In retrospect it is to be wondered that western philosophical thought tolerated such self-limitation for as long as it did. However, the general success of scientific progress in the economic and engineering world gave little cause for hesitation. New attitudes that determined the interpretation of human relationships emerged in new theories of biology and economics that were far from representing a balance between external and internal forces. The only concern with balance seemed to be that of maintaining the balance in favour of the selected fortunate among humankind in the struggle against the blind inanimate forces of unthinking nature.

The heyday of scientific confidence appeared in the mid-19th century. New theories and discoveries of geological transformation, biological evolution and economic development were added to the rapidly growing sciences of chemistry and physics. The new technology of an industrial revolution based on them created new means of manufacturing, and new products. Simultaneous dramatic changes in transportation and communication changed the apparent size and accessibility of the world itself. In most minds this spirit of adventure, discovery and progress was both driven and rewarded by the freedom and objectivity of science. Public debates on the value of science versus religion were increasingly popular in England and Europe during the huge surge of self-confidence that emerged during the 19th century, with science amassing credulity in the process. Irvine[13] shows how important to the popularity of Darwin's Theory of Evolution were the personality clashes between Darwin's principal supporter, Thomas Huxley, and the several opposing representatives of the church, among whom was Bishop Wilberforce, already well known for his crusade against slavery. George Bernard Shaw[14], saw that the acceptance of evolution in science actually depended on its role as an apparently "objective" rationale for the economic laissez faire theories that promoted the industrial revolution and the resulting new wealth of the recently strengthened middle class. The surging rationality was supported by an underlying shadowy irrationality.

Looking dispassionately at the social environment and the popularity of theories of competition and progress, one could hardly be excused for questioning the idea that the Theory of Evolution, or other parallel scientific "advances” arose as glimpses of truth in the minds of independent scientific investigators. It is only in retrospect that it has become possible, even plausible, that the scientific insights that supported the society of the time were simply the predictable reactions of their intellectual and economic climates. In fact, the Theory of Evolution attributed to Darwin on the basis of his submission to the Royal Society of London in 1865, was simultaneously submitted to the Society through an independent, detailed and creditable investigation by Alfred Russell Wallace[15].

This curious and irrational fact about simultaneous discoveries of the theory of evolution, and its responsibility for pivotal changes in societal attitudes, is often still taught as an isolated example of a special event in the history of science. But we know that it is only the most famous instance of the many where science has resulted in the same observations from different isolated studies[16]. Indeed, the fact that coincident appearances of "original" scientific ideas, ostensibly independently developed, occurred had become commonly recognized by the 17th Century to lead the Royal the Society of London to attempt to address it through its rules of priority. These were widely said to be simply rules to guard against plagiarism. The fact that they also indicated a high frequency of coincidence of “new” ideas seems to have attracted little attention. The possibility that the whole intellectual and social atmosphere was the joint reflection of a mentality that supported the consolidation of colonialism from Europe, supported its Industrial Revolution and fed the American Civil War would have required that objectivity be subject to factors of awareness, openness and motivation that were foreign to the prevailing mood of self-confident moral as well as intellectual superiority of the whole 19th century.

The phenomena relating science to its social-cultural milieu were reviewed by Kuhn[17]. He pointed out how the origin of new recognitions rests on a broad base of common experience and functioning. He recognized two interactive phases of science that he called "normal" science, and "revolutionary" science. By normal he referred to the conceptions of a deliberate, rational activity of observation, hypothesis formation and testing. It was dependent on what was called “reasonable.” This corresponds to the still popular conceptions of science, often cited by scientists themselves, particularly in what is known as “bioassay,” as indicating the correct view of all scientific endeavour. In the term “revolutionary”, however, Kuhn recognized that process of discovery of new points of view – this being exactly related to the concept that we are presenting here as the creative irrational. This, from the first, has always been considered by the romantics of science to reflect its true nature. It is not an unintentional result of the discriminatory use of our best reasoning. This is precisely the area of interest that attracted the attention of science greats such as Albert Einstein[18](1879 –1955), Niels Bohr (1885 –1962)[19] Kurt Gödel (1906 –1978) and Jochen Heisenberg (1939 - )[20], to questions about how problems are solved.

The 20th Century Science Revolution

Serious questions of the appropriate place for the human element in science first became significant in relation to nuclear physics. One of the most fundamental questions of physical science was whether observations can be made in the absence of some pre-existent theory. In the science that claims to depend on measurement, at least some theory about measurement systems is called for. Even more fundamental is the question of what is to be measured. Can this be decided without the intervention of the thought and experience of individual scientists? The remarkable observations and interpretations that followed from contradictions between relativity and quantum theory was the specific problem that has brought about the further attempts to bridge the gap between the scientific rules of a search for knowledge and the requirements of a search for wisdom.

Four great discoveries of the 20th century initiated this revolution: 1) the Principle of Relativity, 2) the Principle of Complementarity 3) the Gödel Theorem and 4) the Principle of Uncertainty.

Einstein published his first seminal paper on the Principal of Relativity in 1905 as the “Special Theory of Relativity”. It pointed out that the formerly accepted idea of basic absolute measures of space and time were not needed. This long accepted concept had limited the physical description of the universe to a completely static reference state, which needed instead to understand the world as the fully dynamic place we know it to be. Removal of this limitation was critical to the new development of science as it has appeared in the 20 century. The tone for an enlarged science of physics, and new questions about what we call “Reality,” were finally set by Einstein’s theory of “General Relativity” published in 1915. These two works showed that the classical world of physics as described by Newton, could not account for the major effects of relative motion between objects. In a remarkably clearly written account, Isaacson[21]describes Einstein’s work as an “...effort to come up with a new field theory of gravity and to generalize his relativity theory so that it applied to accelerated motion [the effect of gravity].”

The next new understanding was contained in Bohr’s explanation of his “Principle of Complementarity”, showing that it is necessary to allow for the existence of light simultaneously in two mutually exclusive forms. Bohr's insight, published from the same 1927 conference that Heisenberg addressed, initially seemed to cause little comment from his hearers. That may help explain how he came to later state that the idea for it came to him in relation to reflections on the ideas of "love" and "justice" in the affairs of humankind[22] & [23]. He pointed out that these two different criteria of appreciation of events are widely known to relate to the fullest expression of human relationships, but they lead to different, mutually exclusive interpretations, before they can be adopted and applied. That is, settling between them depends, ultimately, on the intentions of what the observer of the situation deems most appropriate at that time. A choice between them must be made before either one can be applied to a particular action. In Bohr's view this situation was as fundamental to the understanding of reality in science as it is in human affairs. It was left to Bohr to realize its wider relation to argument in science. It was in his wider appreciation of the implications of the implied relation of the observer to what is observed that later led Bohm to state, “We are in agreement with Bohr who repeatedly stresses the fundamental role of the measuring apparatus as an inseparable part of the observed system.”[24]

The third major contribution appeared in 1931, when the Gödel Theorem was published. It demonstrated that it is impossible to test the postulates of a logical system from within that system; i.e. science necessitates the recognition of the observer. The Gödel Theorem was not published until 1931, and while its implications were somewhat more obvious for understanding the nature of the hierarchy of cause-effect relations in analysis, its general philosophical implications were not well spelled out for more than 50 years until the work of Rosen[25].

The Gödel Theorem proved that there is no scientific test of an hypothesis or model possible before the model, with its structure and the implied or "entailed" scale of functions, has been formulated. It is truly astonishing that it had taken so many years for a general perception of the necessity for such an understanding to appear. Only in this way could an acceptable rationale for the inclusion of biology among the quantitative sciences of physics and chemistry be established. Rosen’s seminal work in the modelling of systems in relation to biological problems appearing in systems of living organisms first enabled others to realize the critical place of level and scale of observation in scientific interpretations. He was the first to point out how biology requires that attention be given to variations at the finest scale of observations of particular phenomena, such as in the molecular structures that are now known to govern the rate of chemical reactions in biology. This modelling was essential in order for the outcome of biological processes, hence life processes generally, to be understandable. As Rosen was fond of putting it, “Biology is too complicated for it to be understood by the methods of physics.” because both physics and to a lesser extent chemistry, are dependent on an assumption of homogeneity on the finest scales of the structure of the component reacting particles. Similar insights have been seen in physics as presented in Greene[26]. “Measurement” can never be objective in the sense of being independent of the scientist making the observation!

In the late 1920s came the fourth major discovery, Heisenberg’s “Principle of Uncertainty”. In it he demonstrated that not all measurements necessary for the description of a system are possible simultaneously without changing the system. This was the first serious questioning of measurement as the objective basis for learning. But while it struck at the very base of the whole structure of science, its implications were obfuscated by technical questions about the nature of the measurement system, and the degree of precision possible in any measurement.

The implications of these four major scientific discoveries were not immediately apparent when they were released. But it was only in their light, extended by Rosen’s work, that physics and mathematics could conclude that objectivity cannot be guaranteed by external measurement alone. This interpretation appeared in paradoxes from the false and incorrect dichotomy assumed by 19th and the early 20th century science, to exist between the observer and what he observes. It was believed that only by this separation could there be a certainty of the objectivity of observations. It is with these deductions by the physicists, mathematicians and biologists that the first realization in science appeared that in addition to rational proofs there is a need for those remarkable processes of thought and understanding that give observation and analysis the scale on which to establish the balance: the hall-mark of human understanding and aspiration.

In the conventional rationalist view of science, these modern lines of scientific thought destroyed that most prized possession of "exact" science: a guarantee of its objectivity. The consequences of this simple fact seem not to have been appreciated until the computer raised them in relation to questions of the "computability" of various models. Realization that scientific discovery and proof depend on both conscious and unconscious processes, had finally overcome the anxiety which demanded the security of rationalism. This breech in the rationalist wall, whereby the aggressive early self-limitation that forever separated science from an aspiration to wholeness, was thus removed. Some of the greatest minds had recognized the need for such a point of view, but never before had it become an unequivocal currency.

Levels of Science

The 20th century revolution in science that we have so briefly reviewed provides an unexpected generality to our conclusions about the importance of direct experience as a source of knowledge and the essentially irrational basis of these new and ground-breaking insights into our human worldview. According to this outlook, the concept of different levels of comprehension and the related concept of different levels of observation are equally essential to both the humanities and the core of scientific discovery.

Neither science nor the humanities has yet undertaken a systematic study of the effects of different qualities of observation that appear to be of such central importance. In the remainder of this chapter, therefore, we summarize three major views of the place of quality in the act of observing that can now be seen to be reflected in the work of some of the best and earliest scientific minds. These views have been expressed at various times in the literature, and while all three points have arisen in relation to science by Goethe, Einstein and Bohr, their considerations are clearly not exclusive to it. The prominence that has been given to science is symptomatic of the role that it has been required to play throughout the development of Western culture leading to the present day. It is clearly not due to any inherent characteristics of rationality in relation to life that can be claimed as any special prerogative of science. In fact they present a need for a recognition of the operation of both rational and irrational in our lives.

The first such important statement is the expression by two of the giants of science, Goethe[27] and Einstein, of the necessity for a sense of personal responsibility on the part of the scientist. What they are talking about is, however, not the moral responsibility that is often expressed as a need to prevent possible misapplication of scientific findings in the world of technology. What they are specifically concerned with instead, is the need for scientists to take personal responsibility for ensuring that their efforts are directed to the most comprehensive possible understanding of the reality behind the abstractions that scientists produce. Abstractions are the inevitable result of intellectualizations that arise in the investigations that are science's main activity. The special conditions and language surrounding them make it difficult to see how they relate to our cultural or individual values as human beings. Only experience can help us.

One of the earliest comprehensive statements is that of Goethe. As noted earlier, he is best known for his literary masterpiece, the dramatic poem Faust, which displayed an understanding of the dark and powerful elements of the very soul of man that still has not been equaled in the scientific psychology of which it is legitimately considered a direct ancestor. Goethe was deeply interested in science and its nature, and as a result published his original early studies of the morphology of both plants and animals. Of particular interest here is his attack on the evaluation given to the Newtonian physics of light by unthinking commentators. His remarks were published in Zur Farbenlehre, in 1810. In it Goethe pointed out that the essential and important qualitative attributes of the phenomenon of light are not in any way explained by the analysis of colours in relation to the physics of wave-length. He used this fact to illustrate his view that in order for science to deal with the "reality" that since the time of Newton it had claimed as its particular preserve, each experiment needed to simultaneously be an "experience" for the investigator. He recognized that this cannot happen by accident. If science is to study reality[28], the act of making an experiment also an experience (the term “direct experience” is intended by us to indicate the same thing) required that the scientist accept a responsibility to develop a sensitivity not only to the material and the purposes of the experiments, but to his own nature as an observer. Goethe recognized the science of Newton as an intellectual abstraction that, in spite of the remarkable insights that have resulted from it, invites a deficient attitude towards research from lesser men. In his view, any experimental result that neglects the reality behind the question from which it sprang, rather than becoming a means of understanding it, actually inhibits its discovery. Reality depended on finding that quality that adds this missing dimension to scientific description.

In more recent times, Goethe's proposition about the responsibility of the scientist for the quality of experience in scientific observation is made clearer and more specific through its echo by Einstein[29] & [30] who wrote:

"...Is human reason, then, without experience, merely by taking thought, able to fathom the properties of real things? In my opinion the answer to this question is, briefly, this: as far as the propositions of mathematics refer to reality, they are not certain; and as far as they are certain, they do not refer to reality. It seems to me that complete clarity as to this state of things became common property only through that trend in mathematics which is known by the name of ‘axiomatics’. The progress achieved by axiomatics consists in its having neatly separated the logical-formal from its objective or intuitive content; according to axiomatics the logical formal alone forms the subject matter of mathematics....

"In axiomatic geometry the words "point," "straight line," etc., stand only for empty conceptual schemata. That which gives them content is not relevant to mathematics.

"Yet on the other hand it is certain that mathematics generally, and particularly geometry, owes its existence to the need which was felt of learning something about the behaviour of real objects...."

It would be difficult to imagine a clearer or more rational statement of the need in science, as in all human activity, for that indefinable element of quality that makes the difference between what we usually mean by the dry and unemotional term "observation", and the "seeing", of which Blake speaks in his famous line, "Seeing the world in a grain of sand ... and eternity in an hour". Science in the fullness of its functioning is not by any means irrelevant to the understanding of Universals; this position can only be true of the science that tried to totally limit itself to the rational. This weakness was detected and understood by both Goethe and Einstein.

The time has passed when the term scientist should be used purely to define an adherence to a set of rules in the employment of some technique or other. The parts of science are as different from one another as 19th century concepts of science were from religion. It has been pointed out by Rosen[31], that the analysis of any system into its component parts loses information about the underlying unity, an idea that he traces back to the original writings of Aristotle on the "final cause" in science. Taken together, these parts of the system of learning are simply the necessarily contrasting means at our disposal for the comprehensive study of reality; that in the last analysis depends on development of the observer's capacity for comprehensiveness and reconciliation of opposites.

Plato’s admonition in Timaeus to clarity on the part of the speaker in respect to the purposes and effects of the discussion is far from being an incidental reminder of the nature of the needful correct use of the thinking functions that are alive in us. Clarity of the intent is the second important statement that needs to be involved in the performance of scientific endeavours. The distinction between the use of intelligence and reason seems to agree with what we have already discovered: that there is something of seemingly great importance, additional to the facts, involved in our attempts to distinguish "truth" from "belief". The contrast between intelligence and opinion as aspects of the needed attention to the intentions of our words complements the necessary sense of responsibility identified by Goethe.

The third and final statement about the quality of observation to which we wish to draw attention, concerns the relationship of the individuality of an observer to the collectivity of all observers. It is a question that is raised by Bohr's statement of the exclusive differences between relationships based on love, and on justice. The relationship that we call "love" invokes the weighing of individual human considerations, such as intentions in relation to opportunity, the power of habits against aspirations, or apparent weaknesses against potential strengths. It tries to appreciate another's level of being, and takes account of the limitations of one individual's ability to conceive of another's reality. It invokes Goethe's perceptions of the need to weigh scientific facts in relation to human values, but applies it to the whole question of our attitudes to the fact of being alive in a world with other individual human beings.

By contrast, the rules of formal justice in our exterior world are statistical or aggregate criteria based on consensus. This externalized balancing is far from the delicacy that gives that extra-dimensionality of life to perceptions in the world of love. Our sense of individual being is thus contrasted with the generalities to which the rules of collective justice attempt to give expression. The concept of different levels of thinking, and with it the possibility of different levels in the very sense of existence, play an important role in an approach to how we see ourselves and our world.

A wish to appreciate consciousness requires that we be prepared to understand the possibilities of our world in a more comprehensive, yet more exact manner than has often been invoked for purposes of the scientific description and management of our joint, social affairs. We can conclude from what has been said earlier that this must have been true for Einstein, as it was of Bohr, and of many of those thinkers that have graced the studies of physics throughout the 20th century. To them we must also the add names as early as those of Plato, Meister Eckhart and Goethe who, with those of more recent times, have all explicitly recognized that the direct experiences of our minds, our bodies and our emotions, all need to be combined in some manner that permits agreement within ourselves, and on this basis with one another. This is the real basis for an objectivity of both our rational and irrational sides that may free us to see that we can recognize the most important of universal values in common with fellow human beings. With appropriate help and care, we can perhaps learn to use these perceptions to increase the breadth of our understanding.

The Consequences

Observations from our direct experience show that much of the activity that underlies the whole scientific process is based on the creative irrational and the understanding of the ordinarily unconscious. It is equally evident that what we term "unconscious" informs our rational so-called consciousness, and is in turn informed by it. As introduced in the last chapter, at least part of what the conventions of psychology regard as our unconscious mind legitimately forms the basis for what is truly a larger consciousness than is now widely accepted as the basis for our actions.

It was only after the scientific psychological "discoveries" discussed in the last Chapter that we began to better understand the human connection between new thoughts and the unconscious. Our direct experience suggests that it is foolhardy to underestimate the potentially disruptive aspects of the unconscious. Jung[32] maintained that it is a naïve view that does a serious disservice to the subtlety of human creativity, inventiveness and understanding. Some of the most respected and successful of rational scientists have understood and used their knowledge of unconscious processes as part of their own processes of scientific investigation. This powerful component of our total being can evidently be both an ally and an enemy in relation to maintaining our sense of perspective and aim.

A most interesting feature of this deliberate use of unconscious processes, which may be as frequent in general thinking as it seems to be in science, lies in the results. The solution to the problem, when it appears in the mind of the puzzle-poser, often follows a period of relaxation or actual physical sleep. Its arising seems to be quite independent of, even external to, the puzzle-poser. That is, it comes from an unknown place in us and is virtually always accompanied by a feeling of surprise. Its contents and implications may not always be clearly understood by the recipient of the "insight". It may, however, be recognized as the "right" answer with a degree of certainty that is accessible only to the bearer of the experience. External scientific or mathematical proof and communication rest on the later, slower, rational "working out" that is not a part of the original process of discovery. Evidently there are important unconscious elements of the thinking process which complement the conscious rational activity. They seem to be responsible for at least some of the new perceptions that are an essential part of all learning.

It is in particular the phenomenon of problem-solving that throws additional important light on the unconscious, creative irrational processes, and helps us appreciate the essential complementarity of the various influences underlying our knowledge. For example, certain peculiarities of the dependence of aspects of thinking on unconscious process were pointed out independently by both Einstein and Bohr. Einstein, in particular, noted that solving a problem in science or mathematics may involve a kind of stuffing of the organism's store of memory with everything that seems even remotely relevant to it, like force-feeding a reluctant goose with energy-rich materials. This stuffing of the thinking apparatus is neither desired nor under the full control of the mind, any more than the excess food is desired by the goose. Nor are the precise results predictable. The practice depends on only the most general intentions and attitudes of a "stuffer" who bases his actions on previous knowledge of the value of a resulting “foie-gras” of ideas. Such a view strongly complements that of Plato expressed in the Timeous, which was briefly reviewed earlier, but is often missing from present day common understanding of science.

Einstein[33] made clear his perception of how the intuitive, creative irrational content of science that is the vehicle of its greatest discoveries is not easy to access and involves the deepest commitment and efforts of the scientist. It is discussed in this extract from his writing:

"Only those who realize the immense efforts and, above all, the devotion without which pioneer work in theoretical science cannot be achieved are able to grasp the strength of the emotion out of which alone such work, remote as it is from the immediate realities of life, can issue. What a deep conviction of the rationality of the universe and what a yearning to understand, were it but a feeble reflection of the mind revealed in this world, Kepler and Newton must have had to enable them to spend years of solitary labor in disentangling the principles of celestial mechanics! Those whose acquaintance with scientific research is derived chiefly from its practical results easily develop a completely false notion of the mentality of the men who, surrounded by a skeptical world, have shown the way to kindred spirits scattered wide through the world and the centuries....It is cosmic religious feeling that gives a man such strength. A contemporary has said, not unjustly, that in this materialistic age of ours the serious scientific workers are the only profoundly religious people."

We need to understand the intent of such remarks and learn how to make use of the thoughts and insights to which they point us. As Einstein points out, the processes involved are not due to our conscious mind. It must also be made explicit that this is the truly creative part of our nature. It is why we build the case in this book for the creative irrational as the key to human success. It clearly arises through the insights afforded by some internal mechanism that permits us to connect with our unconscious irrational. The connection, and its implications are experienced before they are actually worked out rationally to the point that it can be expressed by in the language of our conscious minds.

To refer to the writings of Einstein again[34]:

“The individual feels the futility of human desires and aims and the sublimity and marvelous order which reveal themselves both in nature and in the world of thought. Individual existence impresses him as a sort of prison and he wants to experience the universe as a single significant whole. The beginnings of cosmic religious feeling already appear at an early stage of development…. But mere thinking cannot give us a sense of the ultimate and fundamental ends. To make clear these fundamental ends and valuations, and to set them fast in the emotional life of the individual, seems to me precisely the most important function which religion has in the social life of man…they exist in a healthy society as powerful traditions….They come into being not through demonstration but through revelation, through the medium of powerful personalities. One does not attempt to justify them, but rather to sense their nature simply and clearly.”

Such statements are not only reminders of our own inner nature as quoted in Chapter 1 from Philo, but demonstrate the fact that the best of scientists are truly human beings, with rational and irrational parts. Considerations of quality of observation and interpretation that, by the beginning of the 21st century we are finally learning to apply in science, are fully applicable here.

One aspect of this phenomenon requires special attention: The end result is not always in accordance with expectations. In the experience of the authors, in following an initial "insight", it may sometimes be necessary to distrust certain of the “workings-out” or "explanations" of the apparent solution, especially when in approaching the new answer a sense of excitement arises. At such times, the new "answer" that has been developed may be flawed or mistaken. Our personal examinations of this situation show that when there is a contradiction or mistake in the working out of a new perception, it may result in a sense of excitement, without an accompanying awareness that the reason for it lies in the contradiction, rather than in the perception. With the help of an internal observer who can recognize memories of past experience, it is possible to heed the warning that something is wrong. That is, when this excitement arises, examination of the development of the new idea has to be especially carefully undertaken. Without attention to the various levels of the process, solutions developed out of it can become the captive of unconscious personal emotions that may be part of our ordinary, daily context. The result will be a blindness to both the error that has been made as well as to its inconsistency with our aims.

Where the practice of separating an observing thinker from the thoughts that have occurred is not available or not utilized, the so-called new answer may be espoused, guarded and defended by its owner with a special vehemence that is particularly difficult to penetrate by logic alone. In some cases the difficulty of establishing a balance may be frustrated by the "partiality" that is created by enthusiasm. The answer may subsequently be recognized as wrong, but only after the entrained emotions have been spent or otherwise dissipated.

It seems that while a part of us that is outside our everyday consciousness is involved in the act of new thinking, without a particular independent attention to what is happening the whole process quickly loses its initial duality. Unless some aspect of the capacity to observe is present or can be recalled, the thinking-through of the insight then becomes a function of that level of ordinary mind and emotion in which we so often exist. This experience shows that when only one level of perception exists in us, our thinking is captured by other functions, including the daydreamer. The results may have little to do with thinking, and lack the perspective that is necessary to assessing the relevance of ideas and actions to our goals.

In our experience, the phenomenon in which the moment of separation of the discoverer from the facts discovered is lost again, seems to be the rule rather than the exception. In extreme cases the loss of perspective may account for that special vehemence, or fanaticism, with which solutions to problems are sometimes invested by the uncritical recipient of "revelations". But in ordinary circumstances, the state of separation between the observed and the observer does not seem to last very long. Thus, direct experience shows that the thinking process, especially in its associated, more rapid, unconscious irrational operations, is closely linked to the much more rapid emotional functions. When they become dominant, prior attitude and reaction colour the reception of the results of any study and have a strong influence on our judgment of what is relevant to a given proposition. If we are to use only rational thought in the study of the subtleties and complexities afforded by human creations, we need to be very aware of the power of pre-judgment that it may represent. The capacity to balance and integrate new perceptions with an old context may be one of the most difficult but important thinking-related functions that we need to employ for the study of ourselves and the search for the level of consciousness that can lead to higher understanding. But in the present world that begins a new century, the practical consequences that can follow from the faith that was developed towards the discovery aspects of science needs to be seen as the other side of an almost automatic equation of faith in the statistical methods for the employment of science. The failure to recognize the important complementary interactions of these two quite different aspects of science has underlain much of the simplistic argument that has inhibited the recognition and free flow of what might be truly called our "common" sense. The view that unknown unconscious processes affect the whole system and are conditioned by our cultural milieu may have been too difficult a concept for a science that during the 19th century was built on such pride and elitism that it claimed and was accorded the right to special treatment. It continued to be represented as the ultimately independent, objective, if not virtually omniscient methodology for discovery and learning – up until the dropping of the atom bombs. It has since become increasingly clear that the imbalance between science and its application has new and large practical consequences in relation to the modern politicization of environmental sciences. In the same way, it has underlain the sad state of the deterioration of control of international fisheries. The disastrous consequences of that failure in the balanced application of scientific understanding may already have led to a situation in which the natural production processes of the sea have been needlessly put at risk. The same situation is incipient in the current controversies over the control of global warming[35]. But this is clearly outside our aim of attempting to understand the significance of the rational and irrational in relation to the history of human development.

Cautions Regarding Bias in Science

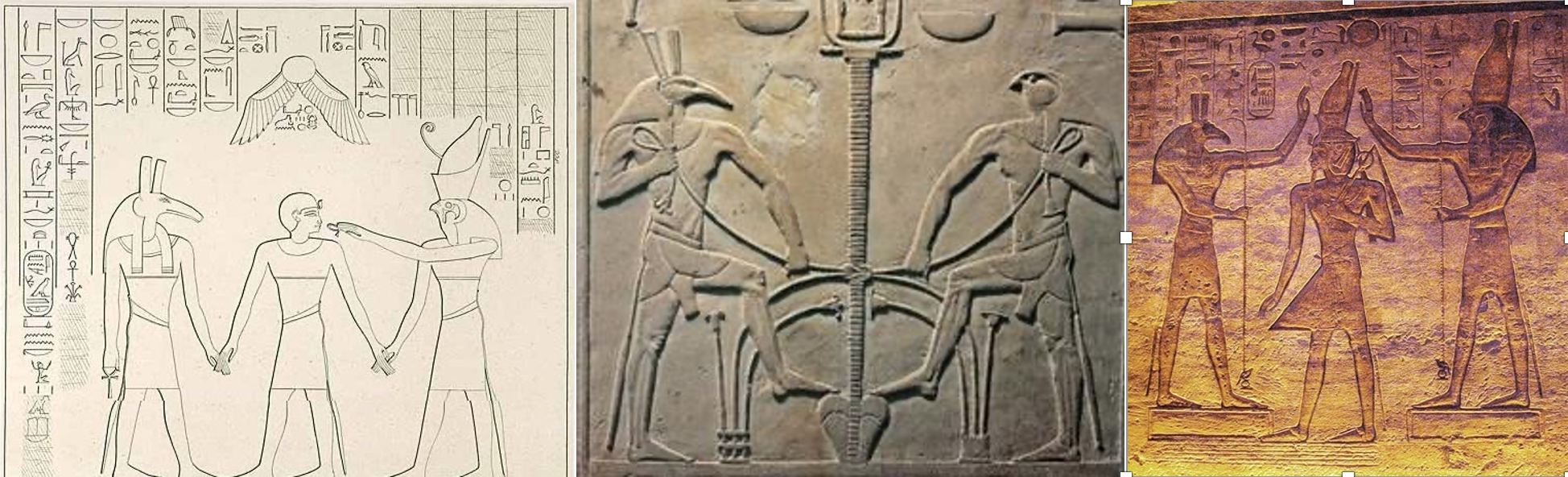

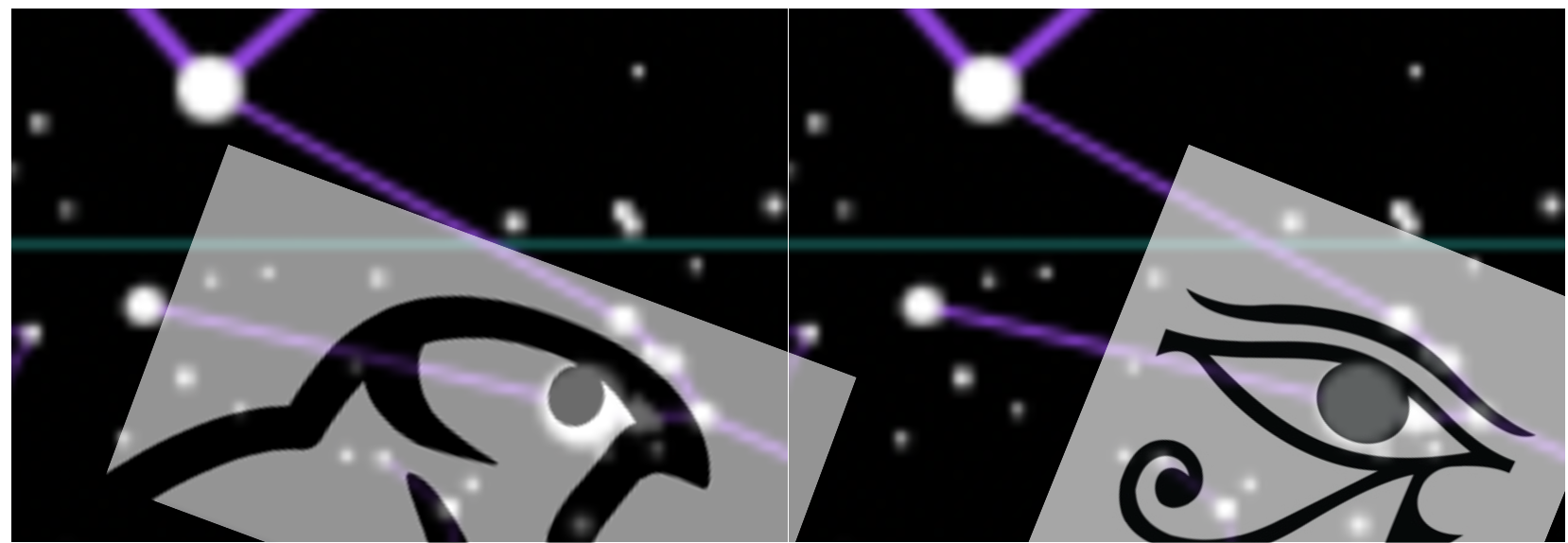

The limitations that resulted from the 19th century sense of superiority and have since been imposed on the abilities of generations of both science and art students to examine different routes to truth, have yet to be fully comprehended. For the purposes of this book in relation to the study of the creative irrational, the insistence of archaeology that it interprets facts of early civilizations "scientifically" as the productions of primitive human beings is important here. This overly popular view has seriously inhibited interpretation of past human creations, and slowed interpretation of its own evidence. For example, it was only in the mid-20th Century that it became well-known that acceptance of the reality of the "mythical" Troy depended on Schleimann's ability to "sell" his ideas popularly[36], rather than on the scientific record. In similar vein, the evidence for an ancient Sumerian civilization should surely have been obvious for many years before it became accepted as the basis for archaeological expeditions of discovery. Similarly, the insistence of early translators of Egyptian myths that they were written primarily as texts to accompany funeral ceremonies has severely inhibited the perception of the shamanic elements that have been recognized by later authors such as Naydler[37] and Brind Morrow. The whole proposition of a text addressed to a dead physical body is clearly different than a text intended for a living person in a state of unusually heightened awareness searching for a more-than-merely personal experience. We are indebted to the more modern translations that deal with this material in balanced fashion and understandingly to demonstrate the effects of an enlarged view of the modes of inquiry that have thus been made available.

It seems to have escaped notice that while 19th century science enjoyed the discomfit it caused for its religious professionals, this same "scientific" society considered its religion and its underlying myth of a possible, if one-sided but direct avenue to truth through science, to be superior to any other. One ironic result has been that professionals and public alike had difficulties accepting the possibility that biblical stories, considered in the 19th century as revelations underlying parables belonging to Judaism or Christianity, could have been copied from the tales of earlier, pre-Christian peoples. The story of the flood first appeared in the Gilgamesh legend dating to the 3rd millennium BCE[38]. It shows remarkably detailed parallels with the Hebrew version, which was not written down before about 500 BCE. Many ingenious rational explanations were offered for the similarity before the simple possibility that the Hebrew version was derived from the Sumerian, as adapted through the Babylonian, was accepted. A parallel new interpretation of early Greek thought has recently been offered by Kingsley[39], and in our view calls for careful study and consideration. It is still not clear whether there has been a direct transmission from the Egyptian to basic Greek outlooks; many prejudices about the Greeks still seem to remain unexamined. It needs to be recognized, however, that the early Greeks obtained their inspiration from Homer, who appears to have known the Troy that modern archaeology places in the 12th century BCE. That is, the time of the epitome of the high civilization of Egypt in the New Kingdom, occurred at the same time that the Troy of Homer was also at its peak. Could they not have had substantial pre-war contacts? Similar phenomena of the insufficient realization of time may underlie delays and arguments that have surrounded the publication of material from the Nag Hamadi or Dead Sea scrolls. Such examples illustrate the difficulties of using thought and reason, in the presence of prior attitude as primary vehicles on the supposed road towards wisdom and consciousness.

These peculiarities of interpretation of archaeological materials are specific examples of difficulties that pervade the scholarly and literary world, giving way only very gradually to the criteria for objectivity advanced by Husserl’s philosophy. They seem all too naturally human versions of what has happened to some of the ideals of scientific objectivity in fields like archaeology and social sciences. These are not naturally “scientific” at their base, dealing as they necessarily do myth and art, with symbolic expression of questions about human values. Such views become of critical importance when they limit access to material, an especial danger when translation of languages is an added issue. In extreme cases they form impassable barriers to the meanings of the symbols and the significance of artifacts.

The determining influence of background and prejudgment on the ability of "explorers" to appreciate and understand the significance of what they have encountered, was drawn with symbolic clarity during the 1992 celebrations of the 500th anniversary of Columbus' discovery of America. Columbus insisted that he had found what he was looking for: a new access to the already "discovered" China. To find what we are looking for may be a major peril to all explorers, requiring that we face the difficult task of determining what it is that we can trust in ourselves. We are only gradually coming to recognize that our perceptions are all too prone to limitations such as show up currently in misunderstandings and unconscious discriminations against "aboriginals", women, or little known religions. Columbus could hardly have realized even the possibility that he would find an entirely new continent! Or could he? He certainly had available to him resources, at least in the way of maps and seamen’s lore, that we know little about.

In relation to understanding the position of science towards the irrational, the outstanding feature of this history lies in the apparent strength of the resistance of accepted science to the countercurrents identified by Kuhn. Science stubbornly distanced itself from traditional questions that stemmed from the longing of humanity for a sense of something higher and more enduring. It maintained its position by insisting that only science fully committed itself to the rational, and that, by definition, only the rational is objective. The foregoing evidences of its irrationality can no longer be dismissed as the actions of aberrant individuals within an otherwise laudable undertaking.

Science has been long in admitting that there are significant effects caused by differences in the quality of its approach to analyses. However, once the importance of a balance between conscious and unconscious/rational and the irrational elements had been recognized, the way to a new evaluation of the significance of science in human affairs has arisen. One of the main results of these revolutionary realizations has been the weight they give to the important challenges involved in the processes of discovery, relative to the better-known scientific activities of testing ideas. The same seems to us to be true of the attempts made to translate and evaluate past human endeavors, especially as we have found it advantageous, even necessary, in the previous Chapters, to utilize archaeological materials other than texts for discerning the nature of some of the understandings recounted in the texts.

It was with this need in mind that we have earlier stated our belief that the field of scientific research and reporting shows signs of the development of a mythology of its own. As an example, we cite here the work of Greene[40]. In the appropriately elegant Preface to this well-written book, the experienced, scientific author points out that the objective of Einstein to “illuminate the workings of the universe with a clarity never before achieved, allowing us to stand in awe of its sheer beauty and elegance” was not realized because there were “still too many unsolved problems facing him”. But Greene goes on to point out that in the half century since, because there have been remarkable developments, and that “physicists of each new generation...have been building steadily on the discoveries of their predecessors to piece together an even fuller understanding of how the universe works.... physicists believe they have finally found a framework for stitching these insights together into a seamless whole – a single theory that, in principle, is capable of describing all phenomena.” He is, of course, referring to what is known formally as “superstring theory[41].”

This book is not the place to try to raise arguments about specific works or even theories of science. In fact, as illustrated in Green’s book, description of some of the recent works of science also necessarily resort to images to serve as the most effective base for interpretations of complex physical phenomena. Some of them are equal in drama and vividness to the descriptions of images of the netherworld or the world of the dead, images used in the literature and imagery over the past 5000 years. It is appropriate to point out how this claim by Greene, written in clear and elegant prose, is also accompanied by descriptions of images that help us understand how the geometry of our multi-dimensional world can be used as analogies with the much higher dimensional relations that are required to predict phenomena in the unified super-string theoretical world of modern physics. We need to maintain our critical faculties in the face of this kind of description.

In fact, the validity of the imagery for such imaginings seems to depend on relatively simple-seeming acceptance of similarities between the concepts embodied in various higher dimensions and their equivalent numerical short-hand as exponents in algebraic equations. It is difficult to imagine any better way to speak about the nature of the abstract notions of unfamiliar behaviours in space and time, first drawn to our attention in the work of Einstein, than has been undertaken here by Greene. Our purpose in pointing to these details is to recognize the necessity for such devices as illustration, metaphor and analogy, if we are to be allowed to follow what can appear to even the best educated non-scientist to be like inherent inconsistencies. But these same problems appear here in these attempts of obviously very competent scholars to communicate complex concepts to a less-educated audience. Ordinary readers, among whom the authors must be included despite careers in science, cannot be expected to understand such special fields. We nevertheless have a need to grasp the gist of the host of facts that inevitably crop up in the persistent attempts of the competent to describe the essence of their understandings.

Intelligent human beings everywhere wish for a glimpse of the unity questioned by Bohr that encompasses both love and justice. It was represented by the Egyptian goddess Maat from over 5,000 years ago. It must surely lie beyond the infinity of all external, exoteric rational analyses. This promise in relation to science is what we call a symptom of the wish for the new mythology of science, as though there has arisen a situation where only one more fact will help us to move towards the necessary union between the inside and the outside worlds that is presented to us by the very nature of existence in our milieu. We shall always have the need to search for that level of being that provides a sense of the meaning of life in the universe.

An Evaluation of Where We Have Arrived

Science, the falsely perceived bastion of objectivity, has now proved the necessity for including the state of the observer in its studies and results. Quantum mechanics has shown the curious physical facts that it is impossible to know both the position and motion of sub-atomic particles. Such findings in the hard science of physics has proven that what is so strongly felt in the humanities has much wider significance. Perhaps surprising to some, science directly supports our search for the wisdom of consciousness and the suggestions about the necessity for its wider scope that is found in past human creations. It is because of the refreshing breadth of understanding of these thinkers of the 20th century that in the 21st century we dare to approach an exploration of the relation between science and humanities, between the rational and the irrational.

To finish off, here we relate a personal story by LMD of seeing Einstein in his natural surrounding in Princeton, New Jersey:

“It was the Spring of 1946. I had just been at Yale for a few months until the first months of my first springtime there. I had made friends with a number of fellow students among whom were some like Jim Barrrow, who had been a graduate student in the Department for a year before me. He had invited me to visit him in Georgia during a Spring break period, and I had been happy to accept.

Jim had already gone home a few days earlier, so to join him I took advantage of the fact that another friend, “Chuck” Huntingdon (whose Father was a well-known Geographer) was driving to Florida. I joined him in New Haven and we set out on our way. That first day we got past New York and were slowly making our way south. He wanted to stop with a relative who lived in Princeton and with whom I was invited to spend the night. I happily accepted and it was next morning that the “event” took place.

We were sitting in the sunny front porch of his aunt’s house finishing our breakfasts. It was beautifully warm and I was able to savour the clear Spring air and chat with Chuck’s Aunt. She was telling us anecdotes about her life there at Princeton.

And then it happened! Down the sidewalk on the other side of the lawn from where we were chatting, Albert Einstein walked by! She said to us, ‘Oh! There’s Professor Einstein! He usually comes by about now’: and there he was! Unmistakably Mr. Einstein! He looked much like a caricature of the man himself. But there he walked; slowly and actually a little absentmindedly along the side walk, perhaps looking just a little lost over some question, but nevertheless quite recognizable with what I thought were old clothes and a pair of slightly mismatched shoes. Already my unexpected trip to Georgia was paying off in unexpected fashion. It didn’t stop there but this event was for me a ‘stand-alone’ that made for adventure.”

Seeing the man himself in his oddly paired shoes left a very strong impression of his life outside the regular norms of modern day life. He was lost in his thoughts. While we may not have fully convinced all readers that we have reconciled science and the humanities in all respects, we trust that we have made it clear that there are misunderstandings of both that cloud their necessary balance in our understanding of ourselves and of humans as a species. We are the result of evolution, but we are also much more than just collections of physical particles.

———- Chapter 11: Creative Irrational in Everyone ——————————————-

——————- Table of Contents ————————————

[1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Humanities

[2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Natural_science

[3] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Francis_Bacon

[4] Einstein, A. 1936. Physics and Reality. J. of the Franklin Institute; quoted on p. 290. in Ideas and Opinions. Bonanza Books, New York

[5] West, J.A. 1973. The Case for Astrology. Pelican Books, Harmondsworth, Middlesex, England. 310 pp.

[6] Irvine, W. 1955. Apes, Angels and Victorians. McGraw-Hill, New York, London, Toronto. 399 pp.

[7] Senge, P., B. Smith, N. Kruschwitx, J. Laur and S. Schlye. 2008. The Necessary Revolution: How Individuals and Organizations are Working Together to Create a Sustainable World. Doubleday, N.Y., 381p.

[8] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dark_Ages_(historiography)

[9] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roger_Bacon

[10] Coplestone, S.J.F. 1993. A History of Philosophy. Volume II, Medieval Philosophy from Augustine to Duns Scotus. Doubleday, New York.

[11] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Meister_Eckhart

[12] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gravity

[13] Irvine, W. 1955. Apes, Angels and Victorians. McGraw-Hill, New York, London, Toronto. 399 pp.

[14] Shaw, G. B. 1931. Back to Methuselah: A Metabiological Pentateuch. London, Constable and Co., 271 pp.

[15] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alfred_Russel_Wallace

[16] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Multiple_discovery

[17] Kuhn, T.S. 1970. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. 2nd ed. International Encyclopedia of Unified Science. Univ. of Chicago Press. Chicago. 210pp.

[18] Einstein, A. 1954, Ideas and Opinions. Bonanza Books, New York. 377pp.

[19] Bohr, N. 1933. Light and Life. Nature 19: 421-423, 457-459.

[20] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jochen_Heisenberg

[21] Isaacson, W. 2008. Einstein: His Life and Universe. Simon and Schuster Paperbacks, New York, London, Toronto, Sydney. 675 pp.

[22] Oppenheimer, R. 1958. The Growth of Science and the Structure of Culture. p. 67-76 in Science and the Modern World View. Daedalus 87(1): 140 pp.

[23] Holton, G. 1970. The Roots of Complementarity. p. 1015-1055 in The Making of Modern Science:Biographical Studies. Proceedings of the American Academy of Arts and Science 99 (4): 732-1123.

[24] Baggott, J. 2011. The Quantum Story, A History in 40 Moments. Oxford University Press.

[25] Rosen R. 1991. Life Itself; A Comprehensive Inquiry into the Nature, Origin, and Fabrication of Life. New York, Columbia University Press.

[26] Greene, B. 1999. The Elegant Universe. New York, W.W. Norton & Co.

[27] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Johann_Wolfgang_von_Goethe

[28] Naydler, J. 1996. Goethe on Science: An Anthology of Goethe’s Scientific Writings. Floris Books, Edinburgh. 141pp.

[29] Einstein, A. 1954. Ideas and Opinions. Geometry and Experience. C. Seelig (ed,) based on "Mein Weltbild”. Bonanza Books, New York. pp. 233-234.

[30] Einstein, A. 1954. Ideas and Opinions. Religion and Science. C. Seelig (ed,) based on "Mein Weltbild”. Bonanza Books, New York. pp. 39-40.

[31] Rosen, R. 1991. Life Itself. A Comprehensive Inquiry into the Nature, Origin, and Fabrication of Life. Columbia University Press. New York. 285 pp.

[32] Jung, C.G. 1958. Vol 7, The Bollingen Foundation, New York. pp. 261.

[33] Einstein, A. 1954. Ideas and Opinions. pp. 39-40, “Religion and Science”. C. Seelig (ed.) This book is based on "Mein Weltbild”. Bonanza Books, New York.

[34] Einstein, A. 1954. Ideas and Opinions, “Religion and Science”. C. Seelig (ed.) based on "Mein Weltbild”. Bonanza Books, New York. p. 38

[35] Lomborg, B. 2007. Cool It: The Sceptical Environmentalist’s Guide to Global Warming. Alfred A. Knopf, New York. 253pp.

[36] Irvine, W. 1955. Apes, Angels and Victorians. McGraw-Hill, New York, London, Toronto. 399 pp.

[37] Naydler, J. 2005. Shamanic Wisdom in the Pyramid texts: The Mystical Tradition of Ancient Egypt. Inner Traditions. Rochester, Vermont. 466 pp.

[38] Dickie, L.M. and P.R. Boudreau. 2017. Awakening Higher Consciousness: Guidance from Ancient Egypt and Sumer. Inner Traditions, Rochester, VT.

[39] Kingsley, P. 2003. Reality. The Golden Sufi Center, Inverness, California. 591 pp.

[40] Greene, B. 2000. The Elegant Universe. Vintage Books, A Division of Random House. New York. 448 pp.

[41] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Superstring_theory

![Figure 38. Titian (Tiziano Vecellio) painting entitled “St. John the Evangelist at Patmos”[1].](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/542d4f86e4b06a71cbdb01c9/1590169487415-E57PZUB1WVNK6GWT6NJO/Titian.png)

![Figure 39. Starry Night by Vincent van Gogh[2].](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/542d4f86e4b06a71cbdb01c9/1590169546263-YYUO7474MGCHC30XYTHD/vanGogh.png)

![Figure 40. The Sistine Chapel, The Vatican[3].](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/542d4f86e4b06a71cbdb01c9/1590169609041-12RAVIZXQNVO10289QJM/Sistine.png)