Endorsement #1: Richard Nowogrodzki

“The material is interesting and deep, the writing is lively, and the illustrations are excellent.” Richard Nowogrodzki, Cornell University.

Dr. Lloyd Dickie in the Hypostyle Hall of the Temple of Karnak, Luxor, Egypt.

Blog #4: Magic by any other name

What can we understand of Ancient Egyptian “spells”? Were they magic, medicine or prayers? Maybe they were all three?

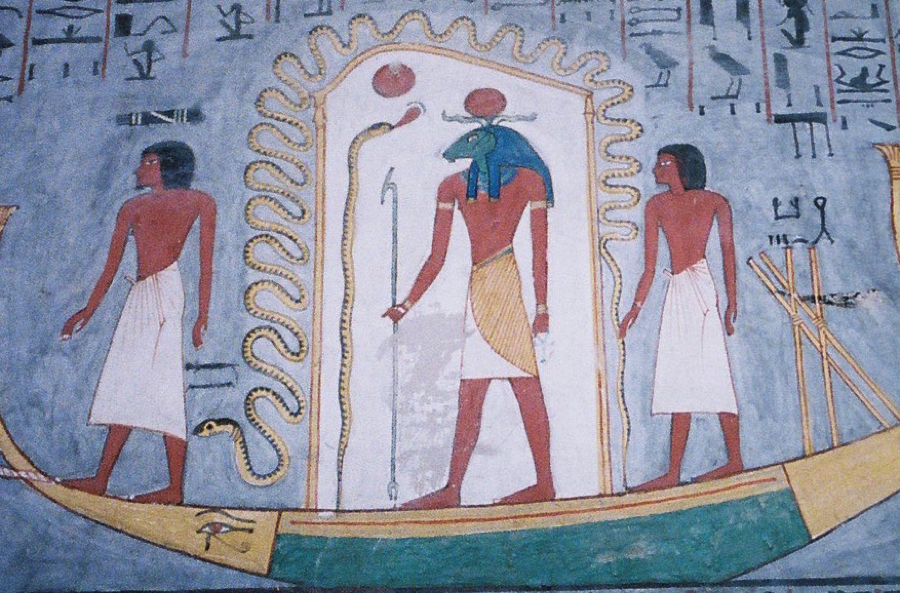

Heka, the Egyptian neter/god of magic, is well represented in the writings of Ancient Egypt from the very beginning of their written literature in the Pyramid Texts circa 2,500 BCE into the New Kingdom writings (Ritner, 1993).

Figure. Heka attending Khnum. Heka appears directly behind the chamber room of Khnum, on the right-hand side, holding the snake’s tail. His hieroglyphic name is to the right of his shoulder. From the burial chamber in the tomb of Ramses I on the West Bank, Luxor.

Heka is recorded as being one of the first neters created after the world was formed. While Maat, the neter of cosmic order, love and justice, is well recognized in Ancient Egyptian culture, Heka her equivalent is rarely discussed. Together they are the first born after the great Atum initiates creation. Heka seems to represent that special spark of life that is necessary to animate matter into life. Literally the name means “activating the KA” or the soul. Versluis (1988) in The Philosophy of Magic emphasizes that the Egyptians considered magic an essential force of life.

So how could the neter of the essential force of life be missed in the general understanding of Egyptian culture? This most likely results from modern day’s difficulty in dealing with the more-than-material aspects of life. We have become a culture of “doubting Thomases” who refuse to believe unless we can all stick our fingers into physical wounds. Our unquestioning trust in science and engineering eliminates any attention to the more-than-physical, such as that which animates life – Heka.

There is no recognized word for “religion” in Ancient Egypt (Naydler, 1996 page 124). It is a modern concept that magic and religion are opposite extremes of one another. While organized religions continue to recite texts for the betterment of individuals and groups of individuals, “magical” texts are seen to be either foolish or aberrant depending on your point of view. Ritner (1993) explores the difficult task of distinguishing magic from established religion. One thing is certain, starting with the Romans, non-orthodox practices were and continue to be suppressed and oppressed. Such oppression was still actively practiced with the persecution of witches into the 1700’s in America and the treatment of Voodoo practices into 20th Century New Orleans. One man’s religion can be another man’s magic – and vice versa.

Magic as medicine: Heka played an active role in Ancient Egyptian medicine with Heka’s priesthood administering to the sick with recitations, application of remedies and articles of belief. Egyptians used both surgical information as well as incantations (West 1993, page 120). While recognizing the obvious medicinal benefits of some medical practices such as setting a broken bone, modern studies are exploring the more subtle influences and benefits of what could be considered magic in health outcomes, such as the known effects of a patient’s positive attitudes. Alternatively, the “broken heart syndrome” or “dying of a broken heart” is an example of a non-physical negative stimulus that results in a very real and observable outcome (http://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-28756374). Chinese acupuncture is only one example of mainstream modern day medical practices that some consider to be operating at the level of magic. While some subtle influences are being recognized as effective in addressing human health, many people around the world continue to purchase and use materials , such as magnet bracelets, that have not been proven to be effective by truly medical-scientific studies. Some modern day medical superstitions, such as the use of endangered animals, even threaten components of our world ecosystem. As with our difficulty in agreeing on the application and usefulness of “magic” in the modern world, it is no surprise that we would have difficulties evaluating the role of Heka in a culture of 5500 years ago.

Magic as magic: There are many examples of scrolls, medallions and objects that were used in Ancient Egypt to promote good outcomes of the Pharaoh and individuals as well as to promote negative outcomes on the enemies of Egypt (Ritner 1993). It is not difficult to find examples of similar beliefs persisting in our modern day world. “Worrying oneself to death” may be an example of the modern day concept of magic. It is hard to know if a voodoo doll would hasten the process. Certainly the belief in the consumption of animal parts for good luck is resulting in real and disturbing threats to present day animal populations, such as some shark populations. Maybe it is part of the human condition to just want to do or believe something – as opposed to accepting a nihilistic point of view in which nothing really maters. Magic plays a role in the outlook of an individual and on societal levels.

So as much as we strive to force concepts into distinct boxes, Heka in Ancient Egypt is a concept that modern society can’t rip, tear and squeeze into a convenient classification that can be denigrated and ignored. Heka was the neter of both magic, medicine and of that which enlivens the soul of every living thing.

References:

Nayder, J. 1996. Temple of the Cosmos. Inner Traditions. Vermont.

Versluis, A. 1988. The Philosophy of Magic. Penguin Books, UK.

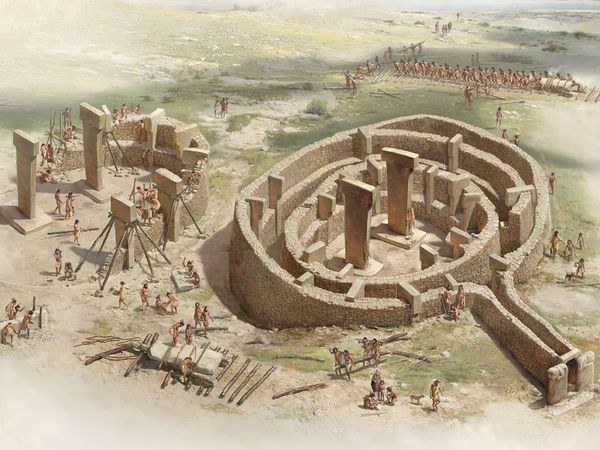

Blog #3: Foundations of modern civilization - Sumer?

Initial development of agriculture in the Fertile Crescent area of the Middle East is often quoted as the roots of our modern day culture. We are also taught in school that the earliest forms of writings ever employed by humans come from the cuneiform system of Sumer who lived in the area. What we are not necessarily exposed to is that the ancient Sumerians invented many other present day cultural concepts that are still seen in modern day Western world, such as schools, libraries, legal writings and importantly philosophy and our worldview Kramer (1956). To properly understand our present day culture and worldview, it is critical to recognize the Sumerian culture as the unique creative and innovating impulse that laid the foundations for our modern day culture.

Cuneiform tablet showing the glyph “An” for sky or heaven in the upper left hand corner.

The Sumerians were a settled, non-nomadic people who survived on agriculture and lived in temple-centered city-states on the banks of the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers. The culture exhibited strong links between social and religious responsibilities. It is likely that the culture existed at least 5,000 years BCE – over 7,000 years ago (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sumer).

While the Sumerians are often perceived as just one of several influential middle-eastern cultures that make up our cultural evolutionary line along with the later Akkadians and the better-known Babylonians, they deserve our special attention as creative innovators who initiated the cultural evolution that continues today in our present day western world.

Identifying Sumer’s real influence on our modern Western culture is somewhat difficult due to the implementations and modifications of their creations by the intervening subsequent cultures of Akkadian and Babylonian.

There existed strong cultural interactions between the Sumer and Akkad cultures. Over the period of the late 3rd and early 2nd millennium BCE, the Sumerian culture both coexisted and was conquered by the Akkadians. There is evidence for bilingualism in the Sumer and Akkad societies (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sumerian_language). While the Akkadian spoken language generally became dominant into the 2nd millennium, the Sumerian persisted as a sacred, ceremonial, literal and scientific spoken language into the 1st millennium (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sumer#language_and_writing).

Already mentioned is the cuneiform writing system that was first developed by the Sumerians. The later Akkadians and Babylonians employed the same cuneiform method of writing.

The same myths and cultural stories are evidenced in all three cultures Sumer, Akkad and Babylon. Although the story of the struggles and successes of the hero in the Epic of Gilgamesh is best known in a single comprehensive Babylonian writing, it originated much earlier in the literature of Sumer in several stories such as “Gilgamesh and the Bull of Heaven” and “Gilgamesh and Humbaba”: http://etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk/cgi-bin/etcsl.cgi?text=c.1.8.1*#

While we trace law codes back to the well-known Babylonian Hammurabi’s Code, they truly originated with the Sumerians. Few of us can name the Sumerian king Urukagina for which there is evidence of his legal code of 600 years before the Babylonian work.

While the extensive interactions between Sumer, Akkad and Babylon tempt one to mash the Sumerian culture into a single cultural concept covering 3,500 years of Middle East history from the peak of Sumerian culture through the Akkadians and Babylonians of the 2nd millennium BCE, it is important to recognize the large differences amongst the three. Sumer pre-dates the Akkadians by at least 1,000 years and the Babylonians by at least 2,000 years. Sumerians were agriculturalists who lived primarily through farming. The Semitic cultures of the region such as Akkadian and Babylonian were primarily nomadic peoples who survived by moving around with their herds of sheep and goats. The difference in languages between Sumer and Akkad required bilingualism in their interactions. Mitchell (2004) highlights the extent of their language differences by stating that “Sumerian is a non-Semitic language unrelated to any other that we know, and is as distant from Akkadian as Chinese is from English.”

It is fortunate for us that original Sumerian writings recorded on preserved clay tablets allow us to explore their culture in great detail. Clay tablets with cuneiform writing have been dated to circa 3,300 BCE (http://etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk/edition2/cuneiformwriting.php). The oldest snippets of Sumerian writing appear as word lists intended for study and practice circa 3,000 BCE (Kramer 1956, page 3). Full historical and literature writings start circa 2,600 BCE.

The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature (http://etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk) provides transcriptions for the various Sumerian literary texts. The site deals with over 400 compositions from the late 3rd and early 2nd millennium BCE. Within the texts provided, there are many themes that modern day readers will find familiar. The original World creation theme from the Sumerian culture is captured in the story “Gilgamesh, Enkidu, and the Netherworld” (http://etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk/cgi-bin/etcsl.cgi?text=t.1.8.1.4#). Here we see the first recording of the separation of the heavens from the earth from the netherworld. In regards to the netherworld, the Sumerians represent it an existence parallel to our regular existence into which beings can journey (“Inanna’s Descent to the Netherworld” - http://etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk/cgi-bin/etcsl.cgi?text=t.1.4.1). The travel and/or existence of beings in the netherworld is similar to what is encountered in the Egyptian concept of the Duat and has some similarities with the much later Christian concept of Hell. The story of the great flood, including the ultimate saving of humans, is captured in “The Flood Story” (http://etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk/cgi-bin/etcsl.cgi?text=t.1.7.4#).

Kramer (1956) presents at least 39 cultural aspects of civilization that were originated by the Sumerians and can still be found in our present day Western society:

- Education

- Schooldays

- Juvenile Delinquency

- International Affairs

- Bicameral Congress

- Civil War historian

- Social Reform

- Law Codes

- Justice and Legal Precedent

- Pharmacopoeia

- Farmer’s Almanac

- Horticulture

- Man’s first cosmogony and cosmology

- Moral ideals

- “Job”

- Proverbs

- Aesopica – animal fables

- Literary debates

- “Paradise”

- “The Flood”

- Resurrection

- Dragon slaying

- Literary borrowing

- Epic literature

- Love Song

- Library catalogue

- “Golden Age”

- “Sick” Society

- Liturgical Laments

- “Ideal King” – Messiah

- Long-distance champion

- Poetry

- Sex Symbolism

- Weeping Goddesses – Mater Dolorosa

- Lullaby

- Ideal Mother

- Funeral Chants

- Labor’s first victory

- Aquarium.

Although separated by 6000 years, the links between our modern world and the developments of Sumer are easy to see and should be given more attention by those interested in our cultural evolution.

References:

Black, J.A., Cunningham, G., Ebeling, J., Flückiger-Hawker, E., Robson, E., Taylor, J., and Zólyomi, G., The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature (http://etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk/) Oxford 1998–2006.

Mitchell, S. 2004. Gilgamesh: A New English Version. New York: Free Press.

Blog #2: WHAT DO YOU KNOW ABOUT EGYPTIAN MATHEMATICS? THEY WERE DIFFERENT, MAYBE THEY'RE BETTER?

Old Kingdom Egyptian mathematics was quite different from our present day view of mathematics (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ancient_Egyptian_mathematics). They used only positive numbers and used only unit fractions (e.g. 1/n). Egyptians pre-1740 BCE, like the later per-Hellenistic Greeks and Romans, had no “zero” character (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Egyptian_numerals#Zero_and_negative_numbers). For these, and other reasons, the Egyptian system of numbers is often seen as inferior to our own. Yet, the Egyptians were able to construct some of the largest and most pleasing architectural structures known to man. We need to better understand and appreciate their system, both for its complexity and for its philosophical basis.

The Egyptians, and later Greeks and Romans, used characters to represent values in decimal systems:

The Roman system addresses the task of tallying, i.e. counting. It uses numerals made up of simple lines and strokes (http://youtu.be/Ik4yloCszYo). In contrast, the Egyptians used a much more complex system of numerals, particularly for characters higher than 100. Their use of a water lily for 1,000, a bent finger for 10,000, a tadpole for 100,000 and a kneeling man with both hands raised (perhaps the neter Heh) for 1 million are much more complex than the simple lines and curves of the Romans. Both the high values and the complexity of the characters of the Egyptian system seem beyond the requirements for simple tallying from which our system is said to have evolved. To even have a character for 1,000,000 is amazing! How long would it take a person to tally a million? At one count per second, it would take 277 straight hours. Why would the Egyptian need such a number?

In regards to the use of a numeral for zero, the Egyptians did use a character for zero in accounting after 1740 BCE: nfr -

The Ancient Greeks avoided the use of a character to represent “nothing”. Early Greek studies in mathematics, prior to the works of Euclid circa 300 BCE, involved both philosophical and mystical beliefs (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arithmetic). It seems that the Ancient Egyptians, and the Greeks who followed, couldn’t see a role for zero or “nothing” in their number system which probably reflects the strong linkage between their use of a number system and its necessary representation of their philosophy and world view. It wasn’t until the time of Ptolemy circa 70 CE that the Greeks began using zero as true numeral in their astronomy: (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Greek_numerals#Zero).

For characters to represent number values the Greeks simply used their alphabet employing equivalence between letters and characters up to the value of 9,000. Our system shows many similarities to the Greek system that provides many numerals for efficient use in arithmetic calculations.

Modern day Western culture uses a base-10 system of numbers for calculations. As a result we use and need to memorize multiplication tables for the numbers 2 through 9. The Egyptians used a methodology based on the doubling of numbers to complete multiplication and division (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ancient_Egyptian_mathematics#Multiplication_and_division). A system based on doublings is a powerful and relatively easy system to use as it requires only the 2-times table for all multiplication and division. It has been suggested that a similar system was used for multiplication of Roman Numerals millennia later. Egyptologist R.A. Schwaller de Lubicz was the first to explore the power of this system in addressing a number of complex algebraic equations with his French publication “Le Temple de l'homme” (Paris: Caractères, 1957) that is now available in English under the title “The Temple of Man (Schwaller de Lubicz. 1998). A system of doubling is reflected in our present day use of the binary system in computer technology.

Geometrically, architecturally and artistically, the Egyptians recognized the importance of using a triangle with sides measuring 3:4:5 to generate 90-degree right angles. Tied to this knowledge of the 3:4:5 ratios, the Egyptians essentially solved quadratic equations (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ancient_Egyptian_mathematics#Quadratic_equations).

Representations of irrational functions are found throughout Egyptian architecture and art. There are numerous examples of the use of the both Pi (π ) and Phi (Φ )in Ancient Egypt (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Golden_ratio). Whereas Pi is taught to all school-age children for the practical calculation of the dimensions of a circle, the lesser-known ratio of Phi, also known as the Golden Section, is not so well recognized in Western culture. This ratio is found in many natural phenomena from biological structures to atomic-scale crystals (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Golden_ratio#Nature). Phi is related to the fibonacci series that is often found in nature: http://vimeo.com/9953368.

Human endeavors by many artists, musicians, historians, architects, psychologists, and mystics have explored the use of Phi in their works.

The Golden Section is the ratio built on two quantities “a” and “b” such that the ratio of the smaller (a) to the larger (b) equals the ratio of the larger (b) to their sum (a+b).

Mathematically, the ratio is irrational with a continuing non-repeating series of numbers to the right of the decimal point: 1.68033 . . . It is thus difficult to deal with arithmetically. Geometrically it is easily dealt with; represented as the ratios of lines, squares and volumes (Lawlor, R. 1982).

As an irrational number, Phi is tied to the concept of creation and generation in Ancient Egypt (Schwaller de Lubicz 1998). Schwaller de Lubicz (1998 page 125) states, “Phi is a function and not a number.” This is an important distinction between the Ancient Egyptian and our present day modern Western systems, where we are interested in calculating particular values, whereas the Egyptian system seems more intent on capturing the nature of the broader functioning of the world around us.

Both the 3:4:5 and Phi functions in Egyptian structures and art were used throughout the 3-millenium duration of the culture starting at least 2,000 years before the work attributed to the Greeks such as Pythagoras that began only circa 600 BCE (Lawlor, R. 1982).

It is hard to believe that the Ancient Egyptians didn’t have an appropriately sophisticated system of math, geometry and algebra when seeing the size, precision and beauty of their constructions. We customarily regard what is early as likely to be primitive and inferior. It is difficult to avoid a pre-judgment of their different, earlier system as being somehow inferior to our later “development”. Thus we highly value our present use of numbers as concrete tools for calculating in an “objective” world. The Egyptian’s developed and maintained a number system for thousands of years that seems to contain subtler and broader meaning for numbers. For example, at one level in their use of Phi that is so wildly seen in the natural living biological world, we can see their attempts to capture a mysterious distinction between the existence of physical matter and the creation of the life-force with its new emergent properties (Schwaller de Lubicz 1998).

As with mysticism, there are suggestions that the Egyptians influenced the later development of the Greek mathematics that are so highly valued by the present-day Western World (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Greek_mathematics#cite_note-LH-2). Thus, Greek mathematics are said to have begun with Thales, who was trained by an Egyptian priest!

In conclusion, it is not a question of whether any one mathematical system is inferior or superior to any other. It is rather a question of recognizing the seeming distance between our calculation orientation and the efforts of the Egyptians to connect with the natural and spiritual world that they considered important. Schwaller de Lubicz (1998) makes the case that in spite of their building prowess, the Ancient Egyptians were not primarily interested in engineering and the concrete physical world. Rather, their aim seems to indicate a desire to capture in their numerical system the broader nature of the creative and enlivening forces that make up us and our world. It is difficult not to agree with him.

References:

Lawlor, R. 1982. Sacred Geometry: Philosophy and Practice. Thames and Hudson.

Schwaller de Lubicz, R.A., 2011. Le Temple de l'homme.

Schwaller de Lubicz, R.A., 1998. The Temple of Man. Inner Traditions.

Schwaller de Lubicz, R.A., 1957. Le Temple de l'Homme, (3 vol. en coffret) Édition Caractère, Paris, 1957. Réédition Dervy Livres.

Schwaller de Lubicz, R.A., 1998. Sacred Science: The King of Pharaonic Theocracy. Inner Traditions.

How old is Ancient Egypt?

Dr. Dickie participated in the field studies of the Sphinx showing its age to be 10,000 BCE at the end of the last ice age. Check out this Youtube video on the work and the conclusions of the scientists involved:

Blog #1: The Greeks we love, e.g. Plato & Pythagoras, gained wisdom from Egypt. They weren't interested in dead people.

In contrast to the prevailing view that texts found in the Old Kingdom Egyptian Pyramids of the fifth and sixth Dynasty were addressed to the dead Pharaoh, there is evidence that the writings played a role in the development of the Pharaoh himself while he was still alive. While the writings in the Pyramid Texts may contain funerary themes, it is likely that they also carry the symbolism of initiation, mysticism and shamanism for use by the living Pharaoh (Naydler 2004).

Although the three Great Pyramids of Giza are often seen as the iconic buildings of the Ancient Egyptians, it is lesser-sized pyramids, beginning with that of the Pharaoh Unas at the end of the Fifth Dynasty, which contain the Pyramid Texts engraved into the walls of the chambers and on the sarchophagi (http://www.pyramidtextsonline.com/index.html). These pyramids are said to be built over a relatively short, early 175-year period of the 3-millenium duration of the Ancient Egyptian culture. There is very little evidence that any of these pyramids contained human remains. In fact, several of the sarcophagi found in the pyramids, which had their ancient seals intact, when opened were found to be empty.

Beginning circa 2345 BCE with the Pharaoh Unas, various compilations of Texts were carved in ten major pyramids. In succession, these are the pyramids of:

- Unas

- Teti,

- Pepi I,

- Ankhesenpepi II (wife of Pepi I),

- Merenre,

- Pepi II,

- Neith (wife of Pepi I),

- Iput II (wife of Pepi),

- Wedjebetni (Wife of Pepi II) and

- Ibi a Pharaoh of the Eight Dynasty circa 2170 BCE (Allen 2005).

While the Pyramid Texts are the second oldest text ever written in the world (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ancient_literature), they present a well developed, expansive list of over 750 well-developed phrases or recitations such as Recitation 536 from (Naydler 2004) that reads:

"My death is at my own wish, my spiritualization is at my own will."

The Pyramid Texts contain many such images and themes that are also found in later Egyptian writing. There is a danger in compressing history and considering all texts written over 2500 years as the same: a) Old Kingdom texts engraved in Pyramids, b) Middle Kingdom texts written on coffins and c) texts of the later New Kingdom included in temples and tombs. The Coffin Texts were first written on coffins in the first Intermediate Period circa 2181–2055 BCE. The best known of Egyptian literature, the mis-named. “Book of the Dead”, more properly entitled “The Book of Coming Forth by Day”, was written at the beginning of the New Kingdom around 1550 BCE, 600 years after the last use of Pyramid texts. While the later writings of Middle Kingdom Egypt are said to include wisdom literature, the Pyramid Texts continue to be considered as funerary in nature (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wisdom_literature). E. Wente (1982) explored the evidence in the writing of the Book of Coming Forth by Day for mysticism in Pharaonic Egypt. He finds multiple references to the phrase “upon earth” in this later Text. It is difficult to imagine this phrase applying to a dead person who has moved off to another world after death.

It is also important to recognize that the pyramids that contain the Texts are found within complexes with several recognizable building structures. On the banks of the River Nile there is a Valley Temple that is the beginning of a long enclosed corridor built on top of a man-made causeway leading up a mortuary temple. This temple attaches to a walled area within which the pyramid proper is built (Naydler 2004). The presence of a mortuary temple within the larger complex is not sufficient to believe that the whole complex is of a solely funerary nature. It is possible to consider multiple uses throughout the complex. For instance, in the modern Western World we would not maintain that a church and its associated graveyard as being strictly funerary, even though they are found in close proximity of one another and present similar images. Similarly, even though the structures within the pyramid complex might use some of the same images, concepts and themes, they may have performed different functions for the pharaoh throughout their lives and after their deaths. It is most likely that the Egyptians buried their dead in tombs, celebrated in their temples and used the great pyramids for their own directed purposes that we are still trying to fully understand.

Dr. Jeremy Naydler (2004) explores the evidence for a mystical tradition in the Pyramid Texts in more detail. His book “Shamanic Wisdom in the Pyramid Texts: The Mystical Tradition of Ancient Egypt” is a follow-up to his PhD. thesis. In his book he follows two lines of argument for a more-than-funerary application for the Pyramids and their Texts in the: 1) repeated references to the well-known Sed festival that was led by a living Pharaoh and 2) repeated references to mystic themes.

First of all, the Sed festival was an important jubilee ceremony for the Pharaohs (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sed_festival). It served to confirm their place in Egyptian culture, and seems to have been celebrated over much of the Egyptian cultural period. This is definitely evidenced in structures that date from the reign of Pharaoh Pepi I, who was the third to build a Pyramid containing the Pyramid Texts. The Sed festival was certainly undertaken by a living Pharaoh. The many references to the Sed festival in the Pyramid Texts, such as written references to the ritual running of the “boundary markers”, the Pharaoh taking on the power of a bull, and the joining of the Pharaoh with the gods. This combination strongly suggests that the Texts in the Pyramid are dealing with a living person, not a corpse. Dr. Naydler suggests that the Pyramid complexes, which include the temple, the causeway, the surrounding walls and the Pyramid proper were associated with the Sed festivals of the Pharaohs who built such structures for use while they were alive.

Secondly, Dr. Naydler finds in the Pyramid Texts repeated themes of mysticism and shamanism. Shamanism is recognized as involving an individual entering a spiritual world or dimension - while alive (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shamanism). The Pyramid Texts contain many phrases concerning the passage of the intended participant into other dimensions, joining with the gods, etc. Within the context of mysticism and shamanism, the Texts clearly state: “You have not gone away dead, you have gone away alive.” (Faulkner 1969).

Naydler’s two lines of argument strongly suggest that the Pyramid Texts and the Pyramid structures, were prepared for use by a living Pharaoh. It is easy to imagine the dark isolated chambers of a Pyramid Complex with its Valley Temple, enclosed connecting corridor and Pyramid to be excellent venues for an initiation process to assist the Pharaoh in communing with the gods. Texts written on the walls would support a pharaoh in his transformation from the earthly world to another dimension, and back, while alive.

Another piece of evidence that suggests the role of a more-than-funerary wisdom in Ancient Egypt comes to us through the Greeks.

Secret initiation rights were well known throughout the Middle East at the time of Middle Kingdom Egypt. For example the Eleusinian Mysteries are said to be the “most famous of the secret religious rites of ancient Greece" (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eleusinian_Mysteries). They began as early as 1600 BCE corresponding to end of the Middle Kingdom and the time of the writing of the Book of Coming Forth by Day. It is certainly conceivable that both of these important ancient cultures were aware of religious motivations and the need to address man’s relation to higher levels while alive.

Greek philosophers, who are much revered by the present day western world, have strong connections with Ancient Egyptian wisdom through reports of their training in Egypt. Thales, who lived circa 624 – c. 546 BCE and considered the first philosopher in the Greek tradition, was trained by an Egypt priest (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thales). Although the philosophers from the Classical Greece culture lived much later in time from that of the writing of the Pyramid Texts, it is important to note that they seem to have been drawing from the same Egyptian traditions and teachings as the Pyramid Texts. It is very difficult to think that the Greek philosophers who have so directly influenced later Western culture would have been so interested in a culture solely focused on death and life after death such as is represented in the writings of the Late Period Egypt tombs from 664 BCE until 332 BCE (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Late_Period_of_ancient_Egypt). It makes much more sense that they were trained in the secret mysterious Egyptian wisdom that related to the higher levels of the Egyptian thought - including mysticism and initiation of the living.

Clearly it is ironic that we revere the Egyptian-trained Greek philosophers, yet relegate the Ancient Egyptian culture to “the graveyard.”

In conclusion, while the Pyramid Texts do contain funerary images appropriate for the final resting place of a dead pharaoh, it can also be seen that they contain images, concepts and themes relating to initiation, mysticism and transformation of a living pharaoh into a person who has experienced the gods.

References:

Allen, J.P., 2005. The Ancient Egyptian Pyramid Texts.

Faulkner, R.O., 1969. The Ancient Egyptian Pyramid Texts, Pyramid Text 213; Unis Text 146.

Naydler, J., 2004. Shamanic Wisdom in the Pyramid Texts: The Mystical Tradition of Ancient Egypt. Inner Traditions.

Wente, E., 1982. Mysticism in Pharaonic Egypt?” Journal of Near East Studies. 41, 161-79.

Table of Contents & Extract on line!

A working version of the Table of Contents and an extract is available online. Download as a PDF @ Inner Traditions: click here

Table of Contents

> Introduction - The Origins of Our Questions

> Chapter One - Life and Meaning in Myth

Unearthing the Evidence and the Methodology of Initial Study

> Chapter Two - Myths of Creation and the Arising of Self

Origins and Evolution of the Sumerian Creation Myths

The Beginning in Sumerian Creation Myths

Comparisons between Egyptian and Sumerian Creation Myths

The Sumerian Creation of Men and Women The Egyptian Creation of Men and Women

The Summing-Up

> Chapter Three - A Dialogue of the Ages

A Conversation between Friends

Final Comments

> Chapter Four - Gilgamesh: The Struggle for Life

The Meeting of Gilgamesh and Enkidu and the

Two-sided Nature of Being

The Character of Enkidu

Aspects of the Foundation of Personality in Gilgamesh and Enkidu

The Partnership Continues

Further Illusions in the Land of the Living

Difficulties of Matching Aspirations with Abilities

The Power of Discrimination; The Story of the Flood

An Important Aspect of the Love of Self

> Chapter Five - Ancient Egyptian Myths of the Arising of Self

Our Basis of Understanding of the Osiris Myth

Myths of the Mystery of Existence in Ancient Egypt

Symbols of Family Relationships

The Myth of Osiris and Isis

The Roles of Osiris and Isis

The Continuing Situation of Osiris in Relation to the Egyptian Experience

A Bald Generalization from the Egyptian Myths of the Mystery of Existence

> Chapter Six - Journeys through the Netherworld

Ancient Egyptian Literature and Tradition on Consciousness

Creation Symbols That Accompany the Creation of Atum The Dwat

Reflections on the Nature and Effects of Entropy Continuation of the Main Theme

Concepts of the “Afterlife” in the Sumerian Tradition

Evaluation of Differences between the Sumerian and Egyptian Netherworld

Egyptian Symbolism of Time A Summary

> Chapter Seven - Search for Wholeness and the Self

Two Principles of Creation: The Personifications of Heka and Maat

The Case for the Importance of Heka

Characteristics of Heka Relating to the Arising of Self

The Relationship between Heka and Maat

The Need to Awaken to the Larger View of Reality

A Final Word

> Appendix 1 - Lineage of Myth

The Egyptian Lineage

The Sumerian Lineage

The Potential for Some Shared Influences Distinguishing Ancient from Primitive

> Appendix 2 - Meanings Contained in Glyphs

> Appendix 3 - Creation Represented in Number Systems

> Notes

> Bibliography

> Index